Developing and

Using Scoring Rubrics

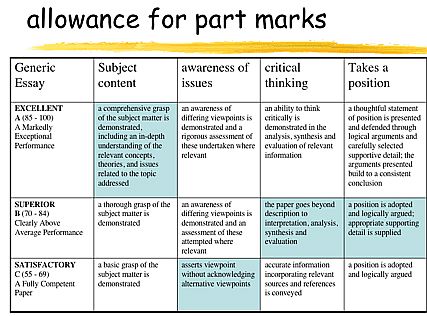

Because the scoring rubric directs student effort by operationalizing the connection between learning and practice, scoring criteria must be clearly specified before students begin work. All rubrics share key characteristics:

The criteria are clearly specified, so that the student and teacher are both completely clear on what is expected and on what dimensions students are to be graded. Note that such expectations may be phrased in such a way as to leave considerable flexibility for students to choose and develop their own content.

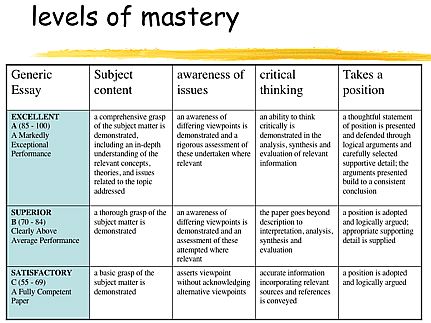

Statements describing the characteristics of student work at each level of achievement form the core of the rubric. Scales can range from three to ten categories; more than ten is considered unacceptable because markers are unable to make such fine distinctions reliably. Three to six categories are most common. For example, 3 categories divide submissions easily into those above average, average submissions, and those below average. A five point scale expands these holistic judgments to include "outstanding" and "unacceptable" categories to either end of the five point scale. An odd number of categories generally produces a normal curve; an even number forces markers to split the class into those above or below some standard.

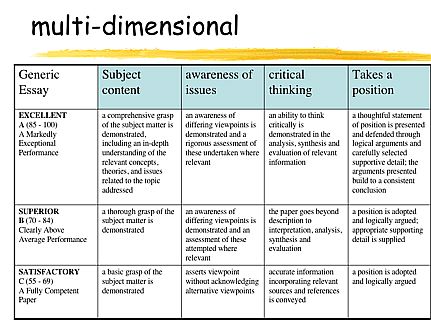

Several dimensions may be specified, focusing attention on a number of separate and distinct criteria in succession. By identifying the separate components or dimensions that comprise the task, expectations are clearer to students, who may then use the rubric as a checklist to monitor that they are adequately addressing all aspects of the assignment. Grading is similarly more precise, accurate, and objective because markers are focusing on only one dimension at a time. (For example, written communication is graded separately from adequacy of the arguments provided; whereas without this separation, 50% of the variance in holistic grading of papers can be explained by spelling and grammar, even where these do not officially count.)

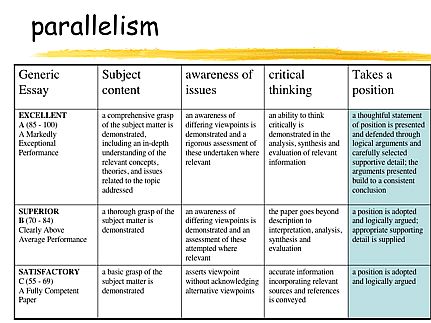

Descriptors are provided for each letter grade or category for each dimension, such that the distinctions between grades for each criterion are immediately clear. In most cases, a chart format is adopted to make this parallelism explicit and obvious.

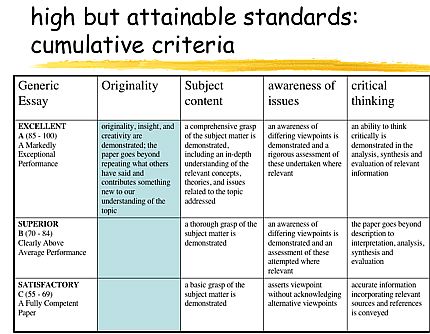

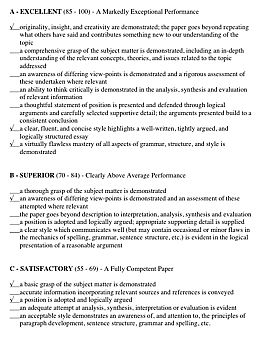

In instructor-designed rubrics, higher categories not only hold the student to successively higher standards on those criteria common at all levels, but may add additional criteria (for example originality, insight and creativity) to the higher categories. Standards are set high, but because even the top category descriptors reflect actual student examples, remain attainable. In the case of student-defined rubrics, the initial drafts are likely to be "all or nothing" criteria unless exemplars, templates or teacher-guided training in rubric construction is provided. Although "done/not done" criteria are sometimes useful for interim steps, the final product is likely to require the development of a more detailed rubric.

Correspondence to the Real World: Teacher-designed rubrics are developed from observing the characteristics of actual student papers; the statements in the rubric reflect the teacher's best attempt to articulate what earned this or that paper an "A" paper or a "C". The object is to develop a marking scheme that matches the observed papers, not to try to force the papers to match the marking scheme. Students may also have a role in developing the scoring rubric, as such participation increases both student understanding and ownership of the rubric. The teacher must be prepared, however, to suggest adjustments that maintain appropriately high expectations in the course, while ensuring student goals remain realistic and achievable in the available timeframe.

Actual student work is unlikely to demonstrate all the characteristics, or only the characteristics, of a single grading category; thus, a student may have "B" content knowledge, "C" writing skills, but nevertheless demonstrate "A" originality. The marker matches salient features of the paper to the descriptors in the scoring scheme, and then quickly judges where the paper falls. For example, a paper primarily described by the statements under "B", but with one or two statements in the "A" category would rate a B+; a paper which matches one "A" descriptor, one "C" descriptor and four "B" descriptors would likely rate a "B". Alternatively, each dimension can be given a specific weighting, so that some criteria (e.g., web page content) can be given more significance than others (e.g., HTML mechanics), and the scores calculated arithmetically.

Rubrics can be re-formatted to facilitate marking, as in this example checklist:

Flexibility: Although student contract rubrics may be appropriately narrow, teacher-designed rubrics require considerable flexibility if they are to avoid dictating specific content and procedures to students. Unless the teacher is prepared to individually design analytical scoring schemes for each new assignment (often, each new student group), care must be taken to ensure the schema can be adopted for several different assignments within the same course (very useful for problem-based learning approaches), or even used in related courses.

Evolving: Teacher-designed rubrics need to evolve as each marking session generates feedback on the rubric for the teacher. As students invent new approaches unanticipated by the current marking scheme, a small percentage of papers may fall completely outside the descriptors; some soul searching may be required to decide whether the paper or marking scheme is at fault. (For example, when students started submitting web pages rather than traditional term papers, major adaptations to paper scoring schemes were required.). As student work demonstrates weaknesses in understanding, the rubric can be adjusted to clarify the need for the missing elements, warn against undesirable characteristics, and solicit desired qualities. Student feedback and suggestions can contribute significantly here.

Ease of Use: Flexible rubrics, as in the example on the next page, allow the marking scheme to be used in more than one context. Thanks to this flexibility and the parallelism that makes it easy to remember, most teachers find that rubrics quickly become internalized by the marker. This greatly increases marking speed, accuracy, and objectivity.