Essential Edits

| |||||||||

|

Memoir and Autobiography Your life is your story. You should tell it.

| ||

|

My father-in-law, some years before he died, decided to sit down and write out the story of his life. He spent over a year writing it, and another four months learning about book binding. He painstakingly printed out and hand-bound each of six copies, which he distributed to his family. Six copies do not qualify an autobiography as a "best seller", but his children and grandchildren cherish that book beyond any they could buy at Chapters.

These days, you don't have to learn bookbinding to produce a book. I often wonder what my father-in-law could have accomplished had he had access to modern print-on-demand or ebook technologies. It is now comparatively easy to produce a book: you just have to want to tell your story. |

My father-in-law posing with a newly arrived plane at the airport he managed. | |

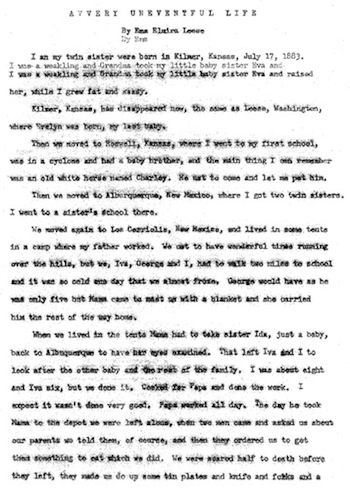

An Uneventful Life?Many people mistakenly believe that no one else would be interested in their story. Take, for example, Ema Elvira Leese, whose seven-page account of her life she entitled, A Very Uneventful Life. Well, if you consider racial tensions, floods, blizzards, small pox, bears, and a mad dog as ordinary, everyday occurrences, then, yeah—I guess not much happened. What was to her nothing much to tell, strikes modern readers as the treatment for a great movie!The moral here is obvious: everyone has a story to tell. Even if there are no big, splashy events that made international headlines, the quiet details of everyday life are often of keen interest to one's descendants; and can paint representative picture of a time and place for the rest of us. Indeed, the things we take for granted and think no one else would care about are often the very thing most likely to capture the reader's imagination. For example, my teenage daughters have a hard time understanding when I explain that there was no internet when I was their age, no personal computers, no phones that weren't hooked to the wall; indeed no TV until I was five, and only one channel until I was their age, and no color until my neighbours bought a frighteningly radioactive set to watch Star Trek. A person paid for each photo they took: the film cost a week's allowance for 12 exposures; a flashbulb could only be used once; developing the film was a separate expense; and it took two weeks to get your film back to find out how your picture came out. Learning photography was a slow and expensive process, even if you could find a camera to borrow. That's hard for my youngest to comprehend when she had already taken 10,000 photos by the time she was six, had seen the result as she took each frame, and it hadn't cost anything because the camera came with her cellphone. When my colleague, Karl Johanson (editor of NeoOpsis Magazine), asked his mother what event had had the greatest impact on her life, he had anticipated something about the moon landings or perhaps WWII, but she told him the most profound change in her life had been the electrification of her town and the introduction of street and house lighting. Because you could suddenly do things after dark. The things we take for granted today—driving, eating meat from animals, going to the store; taking a plane; or using a smartphone—could sound as ridiculous to our grandchildren as an economy based on beaver pelts and canoes sounded to my generation. Exciting TimesOf course, there is much more to people's stories than just the everyday. A memoir is not just about the times you lived in, but about your life and how you lived it: the events that you were part of; the lives you touched and those that touched yours; challenges both over- whelming and overcome; the decisions made and consequences realized. Your story is never just about the setting. Your life is a narrative, complete with foreshadowing and unexpected twists; great expectations and paths not taken; metaphor and simile; heroes and villains. Likely, there was love and laughter, poetry and music, and a certain degree of drama. Car chases and gun play are never requirements for a good life or a good story, and I would not wish them on you just for the sake of having something to say. Big events, fame and infamy, 'tell-all's and insider insights are all very well if you have them, but marriage, the birth of children, school and career, all come with their own brand of adventure, suspense, and, yes, terror. Wherever form your life took, there were people and events worth recording.And even if others know something of the who and the what of your life story, only you can explain the why. Only you know what you knew and felt and figured. Your perspective on events and persons is unique in all the world, and deserves a hearing. Do not hold back. Many people suffer writers' block because they are afraid that if they simply write down everything as they think of it, they might end up saying something they "shouldn't". But trying to censor oneself as one writes is premature: second guessing whether to tell that story or talk about that person starts to restrict the flow of inspiration. Pre-screening every thought, overthinking every anecdote—even second guessing the whole project, if there isn't enough left for a memoir after censoring the "sensitive" bits—inevitably dams the flow and blocks your story from getting to the page. You need to write everything down first to keep the memories flowing, and only later decide whether there is anything that should be cut. And, once down on the page, many people discover that the bits they were worried about do not seem so awful after all. My father-in-law, for example, struggled with whether to include some elements of his WWII experiences that he had never told anyone. In the end, he opted for authenticity and included everything. To his immense surprise, those were the stories that his children loved the best, precisely because they revealed a side of their father never before recognized. Far from being shocked, his kids were immensely proud of their dad for his actions in the war. |

The first page of Ema's typed manuscript.

My dad, with the Edmonton Flying Club on the occasion of the first flight of the Yukon Southern, May 15, 1941. My daughters were startled to discover both grandfathers had been avid pilots. I wish I had had a memoir from my father to better share his story with my kids, who were born decades after he passed. Memoir Needs No EditingIf you read Ema Elvira Leese's piece above, you see that she needed no editing. Writing stream of consciousness, perhaps with some attempt at chronological order, she moves fluidly from time-to-time, place-to-place, jumping from one anecdote to another. It's quite a wonderful jumble of high points and low, of dramatic moments and quiet family times. It's a wondrous patchwork quilt, and patchwork quilts require no editor.And so it always is with diaries, letters, and memoir. Who has ever, upon discovering a stack of letters—a secret correspondence, say, between a relative and a heretofore unacknowledged admirer—complained that the writing was not concise enough, the protestations of love too repetitive, the description of events too self-referential, the content grammatically flawed? That would be as unlikely and intolerable as someone refusing a chest of pirate treasure because the contents should have been stacked more neatly. The important thing is that you write it all down. Spelling and the finer points of grammar, the variety of sentence length, the eloquence of expression, the decision whether to organize by topic or time or theme—none of that matters compared to the more fundamental necessity of getting something down in writing. (Or opt for dictation software on your pc, or say it into a digital recorder—such as these days can be as readily downloaded to your smartphone—if writing does not suit you.)

Writing everything down first is important because many people become so worried about the mechanics of writing or their ability to be 'literary' that they become blocked. In running workshops on writers' block over the years, we have encountered many otherwise perfectly literate and articulate people who are afraid to set pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. We have come to recognize that many of these are still traumatized by their school experience of having their earnest efforts drowned in oceans of red ink by well-intentioned but overzealous writing instructors. One must banish the ghost of one's Grade 6 English teacher from 'tut-tuting' over one's shoulder by uttering the magic phrase, "rough draft". By definition, a rough draft is unpolished, and so exempt from such criticism. And unlike grade school, there is no actual requirement to ever do a second, polished draft. Your descendants will be happy to have any record of your thoughts; there is no need to sweat mechanics or strive for eloquence, unless you want to. | |

|

Of course, the preceding sections are based on the assumption that your intended audience is family and friends. If you want to reach a larger audience, then you may wish to consider getting the work professionally copy edited, and/or working through a second and third draft to further develop and polish your memoir.

| ||

Last updated: March 2, 2018.